Canceling the librettist. Part 1.

You can have any review automatically translated. Just click on the Translate button,

which you can find in the Google button above this article.

Comments are welcome, preferably below this article and not on Facebook, of which most reviewers are not members.

We are 1500 individuals in an opera house, but we are by no means a resistant collective. There are ranks, there are different, sometimes conflicting interests. On the consumer side, we have the audience, who have paid to attend an opera performance. On the production side, a motley crew of more or less creative women and men. Leaving aside for a moment the highly esteemed buffet ladies and ticket takers, and focusing on the artistic side, we see and hear an orchestra, a conductor, the singers, and the chorus. Also present, often posthumously, are the composer, the librettist, and the divine director.

Opera is political

In 1994, Dutch Prime Minister Lubbers announced shortly before the election that he would not vote for the first candidate of his party, but for the third. This was considered a betrayal. The No. 1 was in a hopeless position. In a similar way, but with less knife in the back than the Dutch political rascal of the time, we would like to focus attention on our number three, the librettist, who stands on a modest third step on the honorary scaffold of opera: the composer is just visible in front of him, but the august director, in his ethereal, already multiple award-winning excellence, is far out of sight.

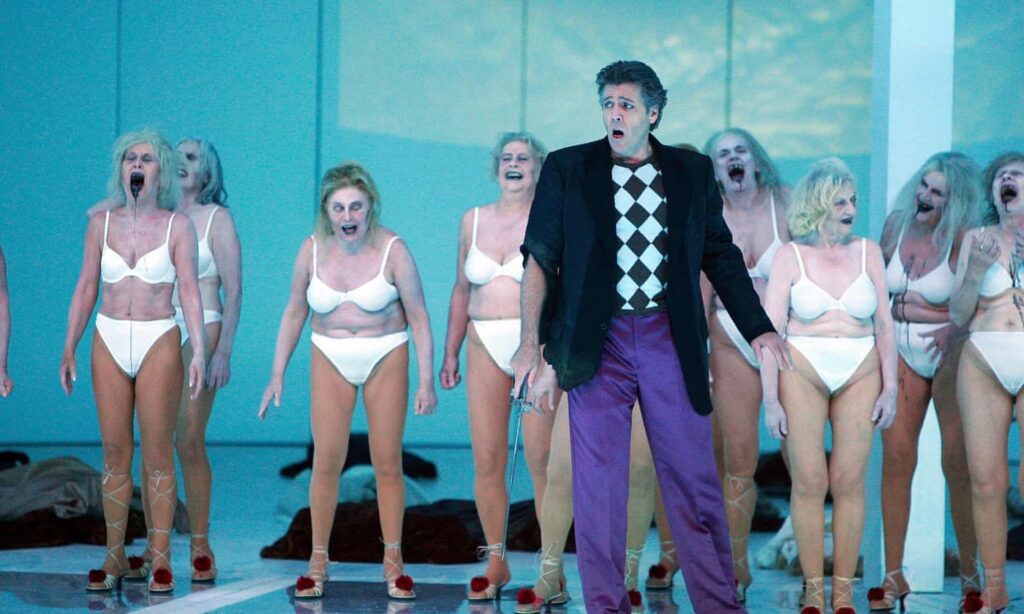

We sympathize with the librettist. He is scandalized, wounded, insulted, grieved and ridiculed, or perhaps worse and more often: completely ignored. He must give way to the shabby backdrop of contemporary social relevance and wokism. A Renaissance palace becomes a prison, complete with inmates in striped prison uniforms. Or worse, they let Martin Kušej or another member of the Director’s Taliban loose on Mozart. The predictability is irritating, the result questionable and more than once distasteful.

Contemporary

Contemporary opera houses take great pains to avoid the label “elitist.” The notion that enjoying the episodic art form of “opera” requires a certain knowledge, education and artistic sensibility should be avoided at all costs. The government’s disgust with this “elitist” idea killed the famous Amsterdam Operette in 2000. The idea that the enjoyment of opera is simply not for everyone is an unpalatable thought to the regents who flaunt their “heart in the right place”.

There are quite a few sincere opera lovers who are not so keen on the so-called “modern views”. To put it mildly. The Facebook group Against Modern Opera Productions has more than 45,000 likes, and in 1994 David Pryce-Jones, British author and then commentator and editor-in-chief of the National Review, took the initiative to create the amusing Association for the Elimination of Trendy Opera Producers. Any director or intendant found guilty by the Association would be immediately and mercilessly executed. A somewhat barbaric but understandable measure, for appeals to common sense or irrefutable arguments could no longer win this battle, as it turned out.

“Don’t try to damage the history of the past.”

Pryce-Jones describes the Association’s visit to Tosca at the MET. And he stages a tirade against the then intendant, Peter Gelb, and the director, Luc Bondy; the latter had long been in the Association’s shadow because of Bondy’s atrocities on his stage in Zurich.

Gelb is quoted in the National Review as saying that he had “always tried to popularize classical music”. According to Pryce-Jones, this is “a sign that Gelb is a populist who is afraid of being seen as elitist. Of course, the “popularized” settings are horribly bleak, and Scarpia is clichédly portrayed not only as the archetypal police chief of an authoritarian regime, but especially as a crude sexual sadist. This silly, one-dimensional interpretation of the character provides an opportunity to introduce call girls (!), one of whom is topless. Tosca ends with a firing squad and summary execution. My association takes note.”

Here Pryce-Jones is right. Puccini was known to be extremely angry at anyone who took liberties with his operas – he left no doubt as to how his operas should be performed.

“Today’s People”

It is a wonderful phenomenon that so many of Today’s People blindly and foolishly accept that a libretto with text and stage directions can be ignored. Fodder for mass psychologists. Or trend watchers. A libretto is an essential part of an opera and cannot be separated from the score. The sometimes idiotic interventions in the libretto always lead to an artistic clash between the music/sung texts on the one hand and the stage image on the other. Remarkable: the more the director deviates from the original libretto, the more often such a clownish hypocrite claims to have put himself entirely at the service of the composition or composer. It’s like the schoolboy who greets his parents with “I didn’t kick a ball through the neighbor’s window today”.

By the way, the lies of clownish hypocrites are not limited to the opera world:

Of course, the libretto almost always came and comes about in close collaboration with the composer, if not the composer himself wrote the libretto, as Wagner did. Out of an “I’d-rather-do-it-myself-then-at-least-I-know-it’s-good” consideration. Words to this effect are also spoken by our housekeeper when, in our kindness, we want to take a small corvee off her hands.

Prima la…. Etc.

Of course, music has (had) primacy in an opera; no one is interested in reading El Trovador by Antonio García Gutiérrez. But the Zeitgeist of first “social relevance” and then the absurd, repugnant “wokism” has turned the opera world into a sinister House of The Damned, in which the fooled audiences are constantly worried about their stamp of “progressive” in the cultural passport. Direction and music, on the one hand, and the libretto, on the other, have thus despicably been made unnatural enemies. A libretto, however, invariably remains the template on which the composer based his composition.

How important the libretto is becomes evident from Schubert’s operatic ramblings: sixteen operas written, none became a success. Cause: lousy libretti (but brilliant music). Mozart had better luck with his librettists; when the paths of Mozart and librettist Lorenzo da Ponte crossed, some absolute high points in opera literature emerged.

Interferences (c.q. changes!) in the libretto are still sometimes defended by simpletons with the argument “but also the librettists were more than once stealing, they stole their libretto from a book.” The book or play as a source of inspiration in no way takes away from the fact that such a libretto is an independent artistic entity, which cannot be tampered or messed with out of considerations of respect and knowledge.

In Part 2 next week, we will give the stage to Verdi, Ricordi, Konwitschny and Puccini. Stay tuned!