Il Trovatore

Los Angeles Opera. Dorothy Chandler Pavillion.

Show attended: 22 september 2021.

MANRICO: Limmie Pulliam

LEONORA: Guanqun Yu

AZUCENA: Raehann Bryce-Davis

COUNT DI LUNA: Vladimir Stoyanov

FERRANDO: Morris Robinson

INES: Tiffany Townsend

RUIZ: Anthony Ciaramitaro

MESSENGER: Orson Van Gay II

CONDUCTOR: James Conlon

DIRECTOR: Francisco Negrín

Verdi’s Il Trovatore suffers from what we might call operatic-middle-child syndrome. Within Verdi’s oeuvre, it falls between Rigoletto (1851) and La Traviata (1853). According to the Opera Sense website, La Traviata is the most performed opera in the world while Rigoletto is the seventh most performed. is the often-overlooked middle child.

Music: 4*

Direction: 2,5*

BEAST OF AN OPERA

Yet Trovatore is not without its merits. In some ways, we prefer it to both Rigoletto and Traviata. The scale of Trovatore is much greater than either of its siblings. The fourth act of Trovatore is one of Verdi’s greatest accomplishments in terms of atmosphere and dramatically effective vocal writing. The problems with Trovatore are the same as its merits. Its scale makes it difficult to produce effectively. Rigoletto and Traviata both require two competent singers and one accomplished singer. If the Rigoletto is an accomplished pro, the show works. There are 10,000 sopranos who can sing Gilda. If the Violetta is a seasoned singer, Traviata works even if the Alfredo and Germont are merely serviceable. Neither show requires a costume change for the chorus. In Rigoletto, the chorus is a group of courtiers from start to finish. In Traviata, the chorus starts at a party and ends at a party.

When it comes to Il Trovatore, four accomplished singers are required. There is a dramatic balance amongst the characters. Manrico is officially the title character, but his storyline is not preeminent throughout. Of all the characters, Azucena’s story is the most central. Her character turns the traditional love triangle of Leonora, Count di Luna, and Manrico into an unequal rhomboid. The chorus in Trovatore is also complicated. It begins as soldiers of di Luna in Act I. In Act II they are gypsies in the first scene. The men then become di Luna soldiers while the women become nuns. At the start of Act III, the men are di Luna soldiers again. At the conclusion of the act, they are gypsies again or perhaps soldiers of The Duke of Urgell, whom di Luna mentions in the first act confrontation with Manrico. From principal cast to chorus, Trovatore is a beast of an opera to produce. How did LA Opera handle the challenge?

SEASONED PRO

Let’s begin with the singers and bass Morris Robinson. Mr. Robinson is exactly the sort of singer we want to hear. He is a seasoned pro with a consistent voice from top to bottom that is energized and fills the house. He was excellent. The only problem is that he was singing the secondary role of Ferrando. The singing of the principal quartet ranged from inconsistent to good to quite good. Before we go there, we must insist that a singer who takes the stage at a premiere house, such as LA Opera, will be compared to all the singers, both past and present, who have sung the role. That is the essence of the opera game. We will go to Trovatore time and time again to hear how each subsequent cast handles these legendary roles.

WEATHERED PRO

Baritone Vladimir Stoyanov, in the role of Count di Luna, sounded like a weathered pro as opposed to a seasoned pro. His top notes were spread and lacked focus. He had all the notes for the role and from time to time he delivered some solid tones but by and large, the voice lacked the powerful lust di Luna harbors for Leonora as he declares, “Ah no! Non fia d’altri Leonora! Leonora è mia!” in Act II, Scene II. The role of Leonora was sung by soprano Guanqun Yu. The middle of Ms. Yu’s voice was pleasant and warm. Yet her technique sounded as if it were based on taking the head register all the way down to the bottom. This resulted in her bottom notes lacking substance and volume. The top notes of the role were all present but inconsistent in their tone. Ms. Yu’s physical performance lacked conviction and presence. In the final act Leonora offers herself to di Luna in exchange for Manrico’s life with the text, ‘Me stessa!” Her gesture amounted to something of a shrug. It was almost as if she was second-guessing the movement. This is Leonora’s defining moment, her moment of self-sacrifice to redeem the man she loves. The moment fell flat. A significant amount of blame can be placed on the production design and direction, but we will get to that later.

Limmie Pulliam, the Manrico for this evening, improved as the night went on. Based on his performance and bio, we would consider Mr. Pulliam to be an emerging artist.

There are several factors that determine the casting of an opera. We are not here to review the circumstances of why a singer was cast. We can only review the singer that is on the stage and the moment often felt too big for Mr. Pulliam. We can confirm that Mr. Pulliam has immense potential and could very well be a world-class Manrico at some point in the future. Manrico’s opening lines, sung from offstage, are a notoriously difficult way to start the evening of athletic singing that the role requires. By the time we got to “Ah si ben mio” in Act III, Mr. Pulliam’s voice had settled but perhaps he overdid it as his first top C in “Di quella pira” was accomplished only after a tremendous effort. Mr. Pulliam vocally nailed Manrico’s defining moment in Act IV when he accuses Leonora with the text, “Ha quest’infame l’amor venduto…”

TONE OF AUTHORITY

The role of Azucena foreshadows that of Amneris in Aida. It requires a singer with tremendous vocal ability. On this night, Raehann Bryce-Davis was up to the task. Her chest register is fully developed, and Azucena’s bottom notes filled the house with a tone of authority and a lust for vengeance as is appropriate.

While Ms. Bryce-Davis delivered a compelling performance, I would welcome an opportunity to see how her Azucena has evolved later this season as she performs the role at Glimmerglass and Nuremberg.

RISK OF BECOMING NONSENSICAL

Throughout the production, a ghoulish ghost figure of Azucena’s mother haunted the characters. It was an effective embodiment of Azucena’s thirst for vengeance. The rest of the production had issues. From what we could tell, the production was divided into four realms. There was the realm of the dead, the realm of Azucena’s mind, the realm of the current action in the story, and the realm of Ferrando telling a tale to three children. This is a strong concept, except for the story-time children, that could have borne significant artistic fruit. However, the execution of that concept was jumbled, self-contracting, and lacking continuity.

Joining Azucena’s mother in the land of the dead was a burnt child of about seven years who periodically walked across the stage. This was supposed to be Azucena’s child whom she mistakenly burned to death. The text of the libretto clearly states that she mistakenly burns an infant and that makes sense. In the confusion of her emotions, Azucena could have mistaken her infant for another. If she had tried to throw her full-grown child into the flames, the boy would have resisted, screamed out to his mama, and she would have come to her senses. We understand that the production is trying to establish a necro-world, but a production must always be based on the text of the story it is supposed to be telling. If it is not, it runs the risk of becoming nonsensical. If a production wants to highlight Azucena’s unstable mental condition, give her a bundle to carry around. In Act II, when she speaks the truth to Manrico, she can reveal that she is carrying the charred bones of her infant. That gives Azucena instability and also keeps the story moving.

The men’s chorus was also relegated to the realm of the dead as a bastardized Greek Chorus commenting on the action instead of being the action. The men’s chorus should help us to follow the story and to differentiate between di Luna’s forces, Azucena’s people, and Manrico’s soldiers. Without that context, events happen on stage without any clear indication as to who has the upper hand. Suddenly in Act III the men’s chorus leaves the realm of the dead and is placed downstage center playing dice before battle. However, they retain their death costumes and makeup. Are they ghouls or not and whose side are they on?

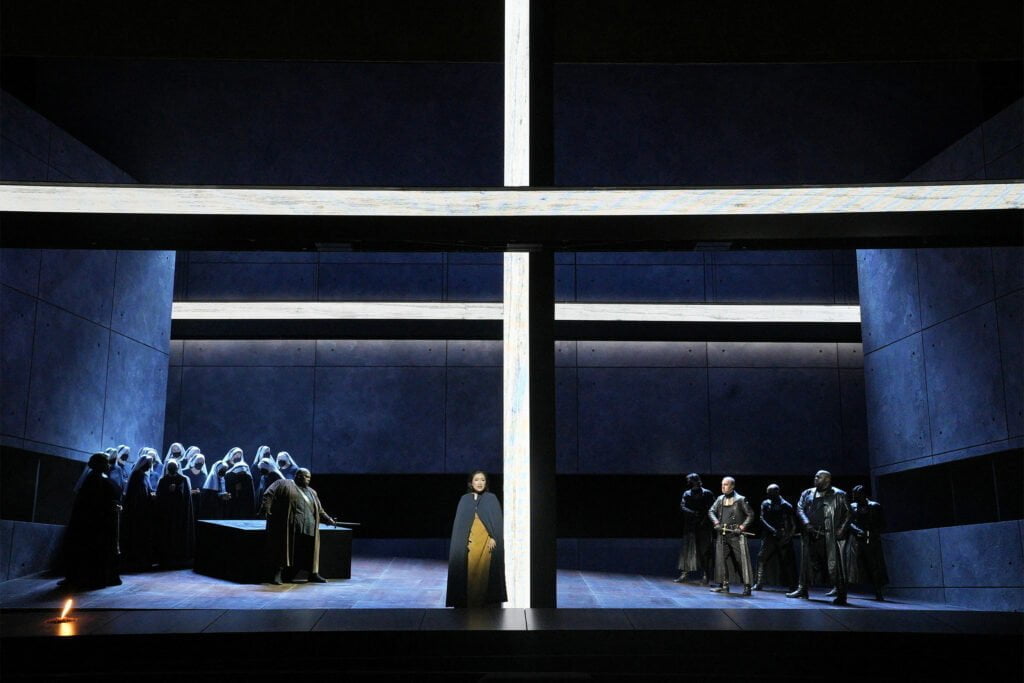

NO SET CHANGES

There were no set changes in the production. There was no indication of a change of setting or the passing of time. A single flame burned downstage right. We thought it was a nice touch to represent the burning of Azucena’s mother and her desire for revenge. Then Ines, Leonora’s handmaid, goes over and warms her hands over the eternal flame. Is the fire representational or literal? It must be one or the other.

A vertical platform created a beam of light that often divided characters in a scene. At the conclusion of Act II Scene I, Azucena and Manrico were split by the beam of light. Azucena’s lighting was green, and her over-grown dead child joined her as she begged Manrico not to go fight. Manrico’s lighting was blue. We liked the idea of being in Azucena’s thoughts as the specter of losing another son haunts her. Suddenly she walks across the stage, through the barrier, and into Manrico’s space. There was no change in lighting to indicate a change in her consciousness or focus. It was arbitrary and destroyed what was previously a well-constructed scene.

ARBITRARY STAGE MOVEMENTS

The entire production was full of arbitrary stage movements based on nothing. Characters crossed from nowhere to nowhere. There was no sense of the space the characters were inhabiting. There was no sense of the time the characters were moving through. At the end of the opera, Azucena is still alive. Verdi’s idea is that she gets her vengeance on the house of di Luna but at the cost of her adopted son. This production steals that hollow victory from her because she had already joined the necroworld. Killing Azucena makes no sense artistically or dramatically. It makes no sense from a narrative or thematic point of view. The only way to kill Azucena is to perhaps have her kill di Luna and then commit suicide after her final line. Il Trovatore is a difficult opera to follow in the first place. When a production removes narrative elements, such as setting and the passing of time, it becomes almost impossible for an audience to follow.

We assume that the production sacrificed the time-tested narrative of Il Trovatore in order to emphasize the themes of Trovatore. Yet the themes are obvious within the narrative structure. They are jealousy, vengeance, ritualistic female execution, motherhood, devotion, and sacrifice.

An effective production supports the narrative so that the audience has access to the themes and then has meaningful conversations on the drive home. An effective production serves Verdi, the singers, and, most importantly, the audience.

GARRETT HARRIS