NORMA. Oroveso once again starts talking about rebellion c.q. revolt against the Romans. Pollione confesses to Flavio that he is fed up with Norma. Norma herself, meanwhile, with apocalyptic predictions about Rome, tries to prevent the rebellion and protect Pollione at all costs. But Pollione wants to flee to Rome with Adalgisa, an intention she rejects out of guilt. Norma then switches from dove of peace to belligerent fury who openly calls for rebellion. Pollione is seized, condemned to the stake and saved by Norma generously offering herself for the fire. Pollione has second thoughts and still joins Norma at the stake. Love literally flares up.

NORMA

Prologue

An operatic overture serves to entertain the audience and marks the transition from everyday life to the theatrical world of opera. First there is the pleasurable feeling of “hey, I sit.” Then comes the mental and emotional preparation for what is to come. Only the orchestra and the conductor play a role here, exactly as the composer intended. The orchestra sets the tone and often introduces important musical themes: there is a slow rising of curiosity. Scenic nonsense that takes place as early as the overture is an unpleasant, common and outdated fad.

This misconception can be even worse: the scenic – in this case, moreover, totally incomprehensible – fuss can also take place before the overture has even begun, resulting in an artistic mishmash that is doomed in advance because it goes down on the hill of good taste. When we experience this misguided phenomenon, we often already know where we stand.

NORMA

Tragedia lirica in due atti. Libretto di Felice Romani, tratto dalla tragedia Norma, ou l’infanticide di Louis-Alexandre Soumet. Musica di Vincenzo Bellini. Creatie Teatro alla Scala, Milano, 26.12.1831.

Muzikale leiding GEORGE PETROU – Regie & kostuums – CHRISTOPHE COPPENS – Pollione ENEA SCALA – Oroveso ALEXANDER VINOGRADOV – Norma SALLY MATTHEWS – Adalgisa RAFFAELLA LUPINACCI – Clotilde LISA WILLEMS – Flavio ALEXANDER MAREV – Symfonieorkest en koor van de Munt – Kooracademie van de Munt – Koorleider EMMANUEL TRENQUE – Productie DE MUNT

Muzsic: 4,5 *

Direction: 1,5 *

Norma

What do Keats, Multatuli, Edgar Allan Poe, Verdi, Anton Chekhov, Couperus, Renoir, Cuypers and Chopin have in common? They were all active in the nineteenth century and the art they left behind — poetry, stories, novels, paintings, architecture and music — still holds an almost unassailable authority today. No aficionado of painting would regard Renoir’s ‘Bal du moulin de la Galette’ as outdated or obsolete. It is all the more curious and illogical, then, that librettists — the artistic co-creators of most operas — are depicted this way. Nineteenth-century intellectual Giuseppe Felice Romani enjoyed fame throughout Europe thanks to his brilliant libretti. He wrote the libretti for Bellini’s Il pirata, La straniera, Zaira, I Capuleti e i Montecchi, La sonnambula and Beatrice di Tenda; for Rossini’s Il turco in Italia and Bianca e Falliero; and for Donizetti’s Anna Bolena and L’elisir d’amore. Bellini did not say to him for nothing, ‘Give me good lyrics, and I will give you good music.’ In Norma, Bellini exploited those texts masterfully. There, too, Romani’s words are inseparable from the prescribed stage setting: the sacred druid forest, the Irminsul oak, the altar, the hills, the forests, and the night fires. Without this setting, the text would lose its meaning. So why is Romani being ignored in Brussels in 2021 and 2025? Because director Christophe Coppens thinks he knows better than Bellini and Romani combined.

Bobby Fischer Teaches Opera

Operas are not timeless objects; they are not templates to be filled in at will, but rather products of specific episodic, social, moral and musical contexts. Those who delve into this context will understand why the characters act as they do and why the score follows or breaks conventions. Without this awareness, opera can quickly degenerate into the pseudologia fantastica of General World Science.

19th-century scores and texts carry built-in ‘laws’: social hierarchy, notions of honour, religion, gender roles and even the pace at which emotions credibly escalate. Overlay a contemporary stage image on top of that and the result is often a paralogous student performance of the kind seen at a Rudolf Steiner school (the so-called ‘raw, edgy stage production’). An aria that calls for ceremony suddenly sounds like museum vocals in a Toyota garage, and a choir that embodies ‘public morality’ stands idle, like an inclusion experience researcher on an average workday.

Musically, Bellini’s Norma is rather ambivalent. Although the orchestration often seems austere and “standard” bel canto on paper, in an exquisite performance the work can be hypnotic. Norma depends entirely on vocal excellence. Bellini’s long phrases are a challenge for singers who do not have exceptional legato. ‘Casta diva’ unfolds deliberately, simply and slowly; however, with too wide a vibrato, the aria becomes a series of loose, beautiful notes.

The same goes for the cabaletta that follows, “Ah! Bello a me ritorna”: if the tempo is too mechanical, the virtuosity becomes routine and the music just sounds sped up “because that’s the way it’s supposed to be”. Moreover, the orchestra in Norma is sometimes considerably less specific than in Verdi, for example. Bellini often opts for pure accompaniment, making the dramatic tension entirely dependent on the singing.

In recitative passages, this can feel “bare” if the conductor does not build up a long arc of tension. Even the bel canto forms of cavatina, cabaletta and stretta can then become structurally predictable.

Vocal lines

However, the above problems become strengths when they are performed exceptionally well. Bellini’s greatest strength lies in vocal lines that stretch emotionally in time rather than embellish, and these lines breathe. “Casta diva” is the best-known example, with its almost sacred mastery of phrasing and the profound impact of small interval movements. Another strength lies in the dramatic vocal combinations, as exemplified by the duet of Norma and Adalgisa. In “Mira, o Norma,” we hear how Bellini composes the reconciliation between the two women as a vocal embrace. Pollione’s part also shows how Bellini poses characters, as in ‘Meco all’altar di Venere’: the tenor is given lustre, but must also be able to ‘bite’ into the rhythm to make the dismay believable.

Norma is not a succession of dramatic moments, but is more like a slowly tightening vise: in the finale, Bellini creates an almost terrifying intensity.

Donkeys

At the premiere of Norma in 1831, the audience was so lukewarm that Bellini furiously left the hall; a day later, he called the audience “donkeys” when the opera was still a triumph.

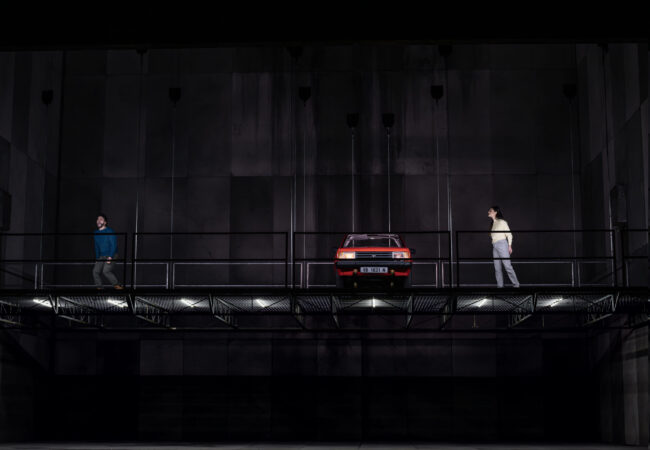

Back to the order of the day. Norma is set in a druidic community in a wooded area, but the performance we attended, a 2021 revival under the same director, was moved at De Munt to a somber, bare, dark space designed by visual artist Christophe Coppens – visual artists, film and theater directors increasingly have side jobs as opera directors. This sometimes leads to surprising finds. So here too: A CAR ON STAGE! The originality of a cremated hot dog. Yes folks, car wrecks and underground worlds! Unfortunately, these are not found in the libretto. In Brussels, no Gauls, lush forests or druidic holy places from the original libretto, but flickering car headlights more reminiscent of the lurid garage from The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

From high priestess to Woman

So Norma is not the high priestess of the druids here, she is primarily a woman who has violated her vows by falling in love with the Roman proconsul Pollione. We suppose: “inner tornness” as wife, mother, mistress and friend? We did not delve deeper into this question.

The Symphony Orchestra of La Monnaie was under the baton of the, in our opinion, never disappointing George Petrou, who – and opera lovers are grateful to him for this – neutralized much of the nonsense on stage by extracting the finest Bellini sounds from his orchestra.

The chorus, the Gallic people (choirmaster Emmanuel Trenque), unfolded an unstoppable flow of energy – unshakable music that revealed itself in popular outbursts.

In Brussels, as in 2021, the role of the motorized Norma was performed by Sally Matthews. Her Norma in Brussels was competent, she sang with a noble sound that suited her role excellently, but which we, conditioned by Deutekom and Sutherland, had to get used to. Moreover, we had the impression that her coloratures, with some nasty outliers, were no longer as fluid as they were four years ago, when we also attended her Norma in Brussels (the above link to Matthew’s 2021 confirms our impression).

The aria of Adalgisa was performed by Raffaella Lupinacci. Her “Sgombra è la sacra selva… Deh! proteggimi, o Dio!”, despite again being sung in a car, provided a moment of overwhelming beauty. Raffaella Lupinacci is a beautiful singer with musical depth and elegance. We tend to the judgment: Lupinacci actually outshone Sally Matthews, but we will never make that judgment because it sounds so unkind. Enea Scala sang the role of Pollione with exaggerated volume (why really?). We noted: beautiful high notes and a less beautiful, but very emphatic vibrato.

Whatever we have to deal with visually,

we’ll always have Bellini.

Olivier Keegel