Der Evangelimann is a lesser-known opera that explores themes such as love and betrayal. With a little imagination, parallels can be drawn with Tristan und Isolde.

You can have any review automatically translated. Just click on the Translate button,

which you can find in the Google bar above this article.

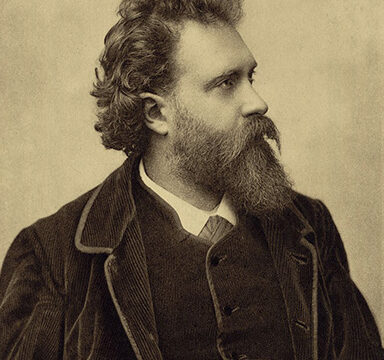

Der Evangelimann, by Wilhelm Kienzl (1857-1941), is the third and most popular of his nine operas. It was first performed in Berlin on May 4, 1895. Karl Muck, to whom the score is dedicated, conducted, and the leading roles were sung by Bertha Pierson (Martha), Eloi Sylva (Matthias), and Paul Bulß (Johannes). It was an instant success and was performed countless times all over the world, even in crumbling Ottoman Turkey, where a special performance was arranged for 500 harem women. (Harem women had nothing to complain about!)

Staged performances after World War II are rare, but we remember one by the Vienna Volksoper in 2005. Occasionally, arias from this opera are still performed, such as “O schöne Jugendtage” and the masterful “Selig sind die Verfolgung leiden.”

The story takes place in a Benedictine monastery in St. Othmar. It is the early nineteenth century. There we find the clerk Mathias, who is in love with Martha, his boss’s daughter. Highly inappropriate, of course, and Mathias is logically dismissed. Now follows a twist that can be called unique in the world of opera. There is someone else in love with Martha, namely Mathias’ brother, Johannes, but Martha wants nothing to do with him. His brother cannot accept this, and in revenge he sets fire to the monastery. (To avoid misunderstandings: this is the action of a lone wolf, not a terrorist attack on a Roman Catholic institution.) A Marinus van der Lubbe-type situation ensues, because it is not the pyromaniac brother but Mathias who is identified as the perpetrator: 20 years in prison, and appeals were not yet possible. After his release, Mathias travels around the country as a preacher. His brother Johannes, a classic villainous baritone, has become a wealthy businessman through dubious practices, residing in Vienna. That he eventually becomes seriously ill is an undeniable case of reaping what you sow. Thirty years after the fire in the monastery, the two brothers meet again. Matthias —a preacher, after all!— forgives Johannes, allowing the latter to die in peace.

“Selig sind die Verfolgung leiden”

Sentimental? Yes, so what? Ever been confronted with the tearjerker La Bohème? The libretto of Der Evangelimann is dismissed by “enlightened minds” as corny or overly moralistic. The story revolves around religious piety, repentance, and forgiveness—themes that “Modern People” consider beneath them. And should Der Evangelimann ever be performed again, you can bet that its content will be turned on its head under the guise of critical reflection.

Der Evangelimann is a typical example of the German late Romantic opera repertoire and is indeed a work of musical and dramatic depth. We detect the legacy of Richard Wagner, with whom Kienzl had a love-hate relationship. The orchestration is certainly Wagnerian. We note: Leitmotifs! Through-composed! But Kienzl places greater emphasis on melodic clarity and accessibility. Accessibility? Of course, “groundbreaking” modern directors don’t care much for that.

Mathias’ transformation from victim to preacher is beautifully reflected in the music: from passionate declamation to more serene melodies. The aforementioned aria “Selig sind, die Verfolgung leiden” is a musical highlight: operatic intensity topped with liturgical solemnity. The aria embodies the central theme of the opera: redemption through faith and suffering. (In a Christian sense, we might add, superfluously.) This hit from the second act, “Selig sind, die Verfolgung leiden,” is somewhat overused, as it is sung again by a children’s choir.

Brother Josef also has his own musical, almost Wagnerian career: he starts as Alberich and ends as Amfortas. Sort of…

“O schöne Jugendtage”. Janina Baechle, mezzo-soprano

The “simple” melodies reflect the rustic setting of the opera without resorting to clichés. The chorus comments on the action and, in this capacity, serves as a moral and emotional backdrop.

Der Evangelimann is often seen as a “conservative” composition compared to contemporaries such as Strauss, but restraint and sincerity also have their value. Kienzl is certainly no “homo chromaticus,” preferring diatonic harmonies that support the text. His orchestration is rich but not overpowering, supporting the vocal lines rather than overwhelming them.

It is very unfortunate and highly unjust that Der Evangelimann has fallen into oblivion, for the opera is a highly valuable example of German opera at the turn of the century. A revival in our time would offer audiences an experience of genuine craftsmanship, rather than the clownery that is being served up in 2025.

The entire opera

Let’s continue with anecdotes, without which the art form of opera would not exist. “Wann geht der nächste Schwan?” Yes, we all know that by now. But Der Evangelimann also has an entertaining side to his priest’s robe, without which this opera might never have been composed. Kienzl wanted to make his third opera a comic opera. His source of inspiration: the stories of Baron von Münchhausen, “The Lying Baron.” But fate decided otherwise. One day in July 1893, Kienzl saw “Aus den Papieren eines Polizeikommissärs” (From the files of a police commissioner) by Leopold Florian Meißner in a bookstore in Munich. He bought the book for 20 pfennigs, thinking he had bought some light reading for his wife. Mrs. Kienzl began to read it and one day she looked up from her book and said, “William, you must read this! This is brilliant drama.” And in January 1894, the opera was completed in a short score; at the beginning of that year, Kienzl played it for the intendant of the Royal Opera in Berlin, Count Hochberg. The work was immediately accepted, and Kienzl was able to begin orchestrating it.

“Aus den Papieren eines Polizeikommissärs” was promoted to a Shakespearean Evangelimann.