Akhnaten is one of Philip Glass’s three large-scale operas based on a “big idea,” in this case monotheism, following Einstein on the Beach, which dealt with new notions of time and space, and Satyagraha, which explored the spiritual and political revelation of non-violence. Satyagraha and Akhnaten, especially, deal largely with the unseen forces affecting the inner (psychological), interpersonal (political), and universal (mystical) aspects of existence, subjects that are uniquely portrayed by the composer’s entrancing musical lines.

Attended by Robert Levine for Opera Gazet, 10 June, 2022

Conductor Karen Kamensek

Production Phelim McDermott

Queen Tye Dísella Lárusdóttir

Nefertiti Rihab Chaieb

Akhnaten Anthony Roth Costanzo

High Priest of Amon Aaron Blake

Horemhab Will Liverman

Aye Richard Bernstein

Amenhotep III Zachary James

Music: 5*****

The Exquisite Rituals of Glass’s Akhnaten in New York

It has been just three years since Philip Glass’s Akhnaten took the Met Opera by storm. Despite the enormous amount of money, time, talent, and thought that went into it, it was expected to be a success d’estime rather than a box office smash. Reports from afar had been glowing, the production having been seen in London and Los Angeles, but New York audiences are sui generis: at once traditional and widely broadminded, who know whether or not Glass’s lengthy, almost libretto-less opera about a forgotten Egyptian Pharaoh would capture the Met audiences. There were fail-safes: Director Phelim McDermott’s spectacular, phantasmagoric, exquisite production, conductor Karen Kamensek’s mastery of the difficult score, the glorious, finely trained and tuned orchestra, Donald Palumbo’s chorus and a quite miraculous cast had been gathered to offer a mesmerizing, deep, and vastly entertaining contemporary masterpiece. And prior complaints about Mr Glass’s repetitive, ritualistic music went out of the window – when I looked around, the audience was more enraptured than during some of the company’s more basic, beloved repertory; indeed, the enthusiasm was comparable only with the company’s earlier-in-the-season Porgy and Bess. For this run, people had heard and there was a mad rush for tickets.

The third in the composer’s “portrait” trilogy which includes Einstein on the Beach and Satyagraha, Akhnaten is the most accessible. The storytelling is direct – the old king, Amenhotep III dies and is buried, his son is crowned and renames himself Akhnaten. He banishes the concept of multiple gods in favor of monotheism in the form of “the sun’s disc,” he weds Nefertiti, he orders a new city to be built in praise of the new religion. The royal couple and their family lead insular lives to the consternation of the citizenry who storm the palace and kill Akhnaten; polytheism is restored, and, in a flash, we are in the present, in a museum, where we learn that almost nothing is known of Akhnaten’s 17-year reign. His civilization has disappeared.

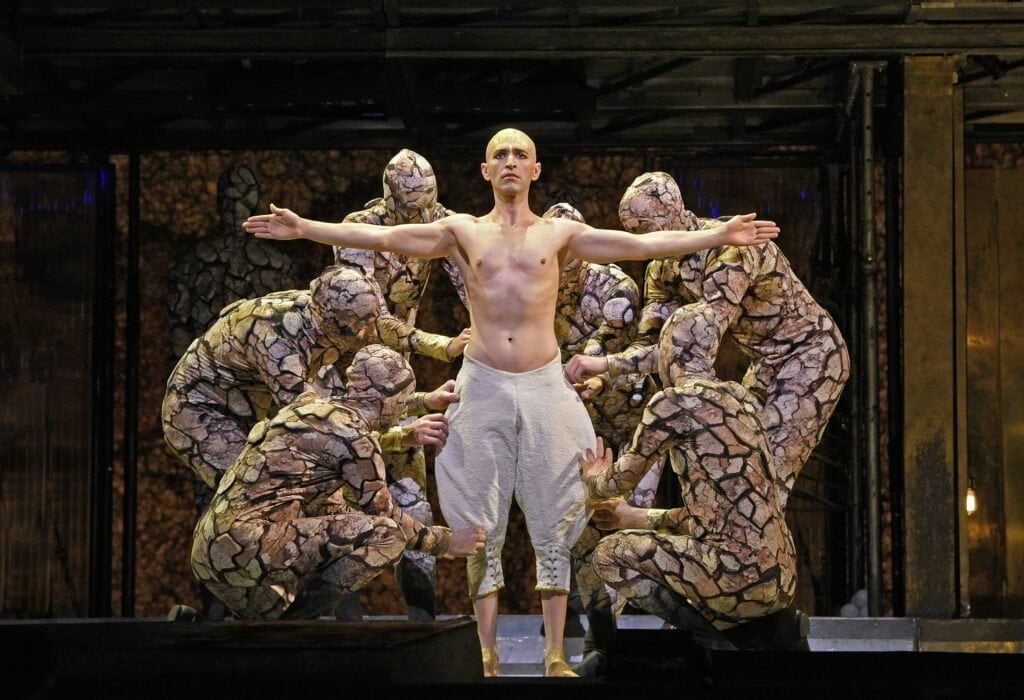

The orchestra is full and the orchestration brilliantly colored; it is scored without violins, giving the work a darkish timbre. The repetitive/variation-on-a-rhythm music clearly outlines the dramatic context and is mimicked by Sean Gandini and his troupe of twelve jugglers, costumed alternately as hieroglyphics or in a type of camo.

Tom Pye’s tri-level set comes and goes and serves everyone well, and Kevin Pollard’s costumes, from the sheer white that originally wraps the naked Akhnaten to the matching bright red gowns for the royal couple in their love duet, to the almost Elizabethan gowns for our boy-king to the spooky look of the couple’s six daughters, elicited gasps of approval. And Bruno Poet’s lighting – oranges, yellows and soft pinks, the latter transmogrifying into astonishing reds, were often underscored by the exotic orchestration and the string of images.

With the exception of some crowd scenes – the burial and the storming of the palace – movement is intensely slow and deliberate, more than a bit reminiscent of the work of Robert Wilson. It is sung in Egyptian, Hebrew and Akkadian which are not translated; the music and action tell us all we have to know. English is spoken by a strong-voiced narrator in the personification of Amenhotep III and sung by Akhnaten in his “Hymn to the Sun” and in the royal couple’s love duet.

Anthony Roth Costanza, whom I first encountered at the 2008 Glimmerglass Festival as Nerone in Giulio Cesare, became a star during the Met’s initial run of performances, and his voice and artistry have become even grander. Both he and his countertenor are lithe and focused, all in the service of the music. His concentration in the death-march movements is staggering and his sound is big and beautiful, having gained volume and breadth. Mezzo Rihab Chairb as Nefertiti sounded warm and lush; Disella Larusdottir’s high, piercing soprano as Queen Tye, Akhnaten’s mother, blended hauntingly with the royal couple in their otherworldly trio. I daresay it was the type of “sound world” most found an unexpected joy.

Zachary James, towering physically above the rest of the cast, spoke Amenhotep III’s narration with grand authority and sang with an impressive, dark tone and Aaron Blake and Richard Bernstein impressed in their smaller roles. Karen Kamensek led with a sure hand, with a blip only in act one’s more frantic moments. She clearly understands the ritual aspect of the score but put great energy into the drama as well, leading so successfully that the audience easily heard the variation as well as the repetition in Mr Glass’s spectacular score. Mr Glass joined the cast for a rapturous curtain call.

All performances sold out.

An excellent review – capturing the grandeur and hypnotic spell of this great artistic achievement perfectly.