Stage Directors

Perhaps the greatest enigma in the operatic world is the elusive “stage director”. Intriguing creatures, coming in a variety of shapes, sizes, forms, and ideologies.

At the turn of the twentieth century, there was no mention of a stage director at all, but rather of a “stage manager”, not to be confused with the all-powerful stage manager of today, charged with running and securing every aspect of a performance. His job was to cart the chorus and supers on and offstage in a timely manner, whilst rather portly solo artists posed at the footlights, gesticulating in a manner one might see in early silent films, often peering intensely at the evening’s conductor during the most intimate of love scenes. The costuming, well-documented in the ancient “Victor Book Of The Opera”, would suggest a grand larceny of all of the draperies in a Victorian funeral parlor. Imagine the dust in all of that velvet…

Starting around 1920 or so, with the influx of brilliant scenic artists and skilled painters, mostly from Italy, a more realistic approach to operatic theater began to take hold. Although the star singers still had something to say about the character they were playing and when and how they could be expected to move during difficult passages, it was now considered valuable to actually use a separate “stage director” to actually stage an opera, thereby pushing the rather static “masque” into a well-needed grave. These stage directors were often very workmanlike, relying on simple, direct moves, entrances and exits, still largely focusing on the main protagonists and keeping the choral artists mostly in the background, as decoration. However, Bohème DID look as it should, and most standard pieces were immediately recognizable. A “craft” was born.

This stayed more or less the same until the early 1950s, with the advent of “TV Opera”, live broadcasts of different pieces, shot in studios with much more close-up work and need for attention to detail. The opera director often came from musical, or from the budding new television industry. Characterizations became more variegated and subtle, requiring a deeper approach, more refined, in sharp contrast to the sweeping gestures and exaggerated mimic often required in large theatrical spaces. A more humanistic and homogenous theatrical concept was being developed. Stage directors now just didn’t deal with “stage traffic” but also had heavy input into characterization and subtler effects. The downside is, of course, that the input of the singer was not always honored, as had been largely the case before. Chorus artists also developed into sub-characters during this era, becoming more involved in the actual plot, instead of just acting as mere commentators from the rear of sides of the stage. Theater was born.

The Advent Of Regietheater

Around the mid-1970s, a change began to take hold. First smaller opera companies and University opera workshops started to take “new inroads”, professing to delve into the “inner meanings” and passive-aggressive socio-political aspects of the piece at hand. At first, the aberrations were subtle, not interfering with the score, but still puzzling to the operagoer. For the most part, even in the USA, productions were not veering too far from the beaten path, I should dare say due to the need for ticket sales and not wanting to risk the wrath of private and corporate sponsors making this VERY expensive art form possible.

Enter Germany, stage right. During the later stages of the long-gone industrial boom, there were theaters in every town. Even the small theaters were producing charming small productions of smaller pieces, Singspiele and Operettas, playing up to 5 times per week, often twice on the weekends. As much attention as possible was paid to casting the roles in a vocally appropriate manner, paying attention to the “Fach System” of categorization, vocally, which I consider flawed, but certainly preferable to haphazard role assignment. In the beginning of the 1980s, a new group was formed under Pina Bausch, producing avant-garde productions which were quite shocking at the time, leaving the public rather bewildered, while a small group applauded furiously, screaming “bravo” whilst looking at the rest of the audience as if they were intellectually challenged due to their bewilderment. I had the immense, if dubious, pleasure of experiencing several of these masterpieces in person. If questioned, the stage director in question usually just shrugged and said that the public just wasn”t educated enough or mentally capable of grasping his or her “concept”. Always nice when the paying public is accused of mental incompetence, I’d say.

With the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the rejoining of the FRG and GDR into one unit, another “problem” was solved. Those in the East, who tended to be skeptical of the “new inroads in opera” preferred to remain more traditional, eschewing the modern Regietheater style. No problem. The powers that be had the solution. They declared some theaters to be technically outdated and closed them. In some other theaters, entire divisions (Opera, Ballet, Straight Theater) were removed entirely, or smaller theaters were merged with theaters in a neighboring town or city. More and more, the Theater directors, many of whom had been artists themselves, were replaced with bureaucrats whose knowledge of performing arts was often sorely lacking. Many of these positions were filled as political favors as well.

Necrophilia

Enter politics. Now that many theater directors were being used as subordinate political puppets, they were subject to the will and whims of the politics of the day. The shift to neo-liberal Regietheater had been accomplished.

Now that the political will had been cemented, the stage directors felt they had a free hand, often to abuse the pieces to be performed, a process I often likened to necrophilia, as the composers of the great works were often long dead and had no means to defend themselves from the de facto desecration of their works, or to mistreat and misuse the performing artists in every way imaginable, both on and offstage. This without ANY fear of retaliation, as the artists are all too aware that any complaint will likely result in their being labeled as “difficult”, “hard to work with”, “unstable”, etc., which often leads to being let go, or blackballed, or both.

Inasmuch as most theater directors in the German-speaking theaters are political appointees, it can often be assumed that many are merely following the instructions of their handlers. In many cases this was very rewarding. In one large city in Germany, the theater director made nearly twice as much per year as did the mayor. Another director of a large European theater also does stage direction there, at an extra cost of up to €75000 per production.

“That’s where the CD ended”

The new inroads into opera theater brought a new sort of opera director into the spotlight. One I remember had chronic sinus trouble and had sudden strokes of genius during staging rehearsals, changing the entire concept of a difficult scene after having rehearsed for several hours, only to then again change half of it at the dress rehearsal. Another blamed everyone else for his raging incompetence, so that when the entire male chorus trudged silently onto the stage at 10 in the morning, glaring at him without a sound, his first words were “quiet, please”, instead of “good morning”. Another took a smile as a direct attack, while commenting with foul humor regarding everyone and everything using language and slurs better kept to the local pub. Others were so obsessed with their brilliant concept that they studiously ignored even the most basic principles of personal hygiene, making working in close quarters a trial by fire. Another requested the very famous conductor “stop the music” until the protagonist was in place on the top of a hill. Yet another, seldom sober, was asked why the intermission to Fledermaus was in such an unusual place. His answer? “That’s where the CD ended”.

Around the turn of this century, the job of the stage director started to become so bizarre that I personally wondered if their productions were being used as therapy to relive the trauma of deep-seated psychological problems rooted in their childhood. I found this rather odd, as mental health assistance is covered by mandatory health insurance in most of Western Europe, to date.

At any rate, I should venture to say that at least 50% of the operatic productions mounted in Western Europe have become largely unrecognizable. The singers have been degraded to conformity-based puppets, vocally and histrionically, the chorus is often dressed in unisex grey or required to act as acrobats during extremely difficult passages, or both. Bizarre headpieces contribute to the singer’s inability to hear, or scrims and veils make eye contact nearly impossible.

Scenery has become, in many cases, less costly. 20 army cots, a bucket of stage blood and a dead animal draped over a broken wooden chair in the corner can be reused at will. Combine this with a few projections on the rear wall, wild gesticulation, and concerned looks, you have an “Evening At The Opera”. Suggestions of various sexual aberrations at inappropriate moments are often welcomed as well.

A Few Code Words To Assist

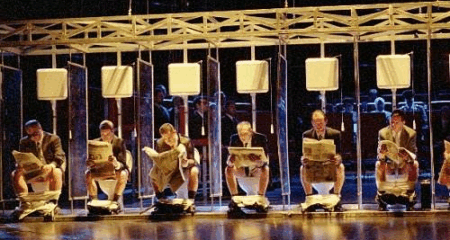

Aesthetic = Garbage Dump or toilet onstage….

Gripping = A number of people are executed onstage, while the main characters up front are urinating into the wings.

Innovative = Nothing to do with the work at hand.

Puristic = The setting is SO generic you could use it for anything.

Moving = The audience moved out of the theater at intermission.

Compelling = Appalling

Genius = Those without visible talent should direct the show.

Challenge to singers = Exploiting those who need to pay the rent.

Attracting a young audience = Driving children away from culture.

Unorthodox stage director = Can”t read music.

Open-minded audience = Brainwashed sheep.

“A fine director and a pleasure to work with” = No discernable talent and very unpleasant.

The list goes on, ad infinitum…

Purpose

What, you may ask, is the REAL purpose of Regietheater? Those sitting at the VERY top no longer care to foot the bill for art and culture. The method, then, is to destroy it, piece by piece, until the audience stays at home, rummaging through their audio recordings and dusty DVDs, looking for a taste of art from a bygone era. The stage director of Regietheater? He/she doesn’t care. They pick up their cash at the premiere, drink their champagne at the afterparty, and leave the running of the piece to the stage manager and a badly underpaid and overworked assistant director, whose job it is to hold the house of cards together, for the entire run of the piece… Eventually, state support for the arts in western Europe will be declared “unsustainable”, due to lack of public interest, and the theaters will, one by one, either be privatized, or closed. A sad state of affairs, indeed.

Opinions expressed here are only my own, most gathered from personal experience over decades of active work in major opera houses.