Die Fledermaus

Operetta in three acts. Music by Johann Strauss II (1825–1899). Libretto by Karl Haffner and Richard Genée. World premiere: 5 April 1874, Vienna.

Performance on 7 December 2025, 18:00 (Première), Zürich.

Conductor: Lorenzo Viotti Director: Anna Bernreitner Gabriel von Eisenstein: Matthias Klink Rosalinde: Golda Schultz Adele: Regula Mühlemann Frank: Ruben Drole Prince Orlofsky: Marina Viotti

Alfred: Andrew Owens Dr Falke: Yannick Debus Dr Blind: Nathan Haller Ida: Rebeca Olvera Skuld (Future): Lucia Kotikova Verdandi (Present): Melina Pyschny Urd (Past): Barbara Grimm Zurich Opera Orchestra, Zurich Opera Chorus, Extras’ Association at Zurich Opera House Set and Video Design: Hannah Oellinger, Manfred Rainer Costumes: Arthur Arbesser Lighting Design: Martin Gebhardt Choreography: Ramses Sigl Chorus Master: Ernst Raffelsberger Dramaturgy: Jana Beckmann Dancers: Sara Pennella, Sophie Melem, Gabriela Hinkova, Sara Peña, Pietro Cono Genova, Roberto Tallarigo, Daniele Romano, Lukas Bisculm

Musik: 5*****

Regie: 5*****

At the start, we were delighted to see the curtain remain closed – a beautiful, classical gesture that allowed the overture to unfold its full effect without distraction.

However, after only a few bars, the curtain rose and a film (Video Design: Hannah Oellinger, Manfred Rainer) was projected, beginning with a view of St Stephen’s Cathedral and clearly intended to set the scene in Vienna. We saw young people in a champagne bar, a nightclub singer, and a band wearing animal masks. This cinematic opening felt unnecessary and detracted from the superb playing of the Zurich Opera Orchestra under Lorenzo Viotti’s direction.

Technical brilliance

Musically, the evening began in splendid fashion: the opening of the overture was clear, technically flawless and articulated with precision. The pizzicato strings at the start, however, could have been more prominent. In the transitions between sections, a little more flexibility in tempo and phrasing would have been welcome; at times, these passages felt somewhat perfunctory. The waltz sections were played straight, with little of the characteristic Viennese lilt – that subtle anticipation of the second beat which gives the waltz its unique swing was barely perceptible. As a result, the overture overall felt a touch too linear, albeit executed with remarkable technical brilliance.

The orchestra’s greatest strength lay in its cohesive sound: the strings played with warmth, clarity, and homogeneity, particularly evident in the arpeggio passages towards the end. Even the notoriously tricky final section, where piccolo and strings race together at breakneck speed, was handled with aplomb. Despite a few interpretative wishes, the overture left a thoroughly convincing impression.

In the first act, one might have wished for a more distinctly Viennese set; the scene was difficult to place both stylistically and temporally, lacking the local color that so often gives Die Fledermaus its charm. Nevertheless, the direction provided plenty of entertainment with original ideas: a brief “Britney Spears moment” between Alfred and Rosalinde injected a wink of humor and proved that Golda Schultz and Andrew Owens could party just as exuberantly off the opera stage.

The immediate plunge into the drinking song, bypassing the usual orchestral introduction, was also surprising. The idea of having Alfred – portrayed by Andrew Owens with vocal brilliance and comic flair – compose the drinking song for Rosalinde live at the piano was inventive, though one did miss the classic pizzicato strings that lend the introduction its special appeal.

Nothing to criticize

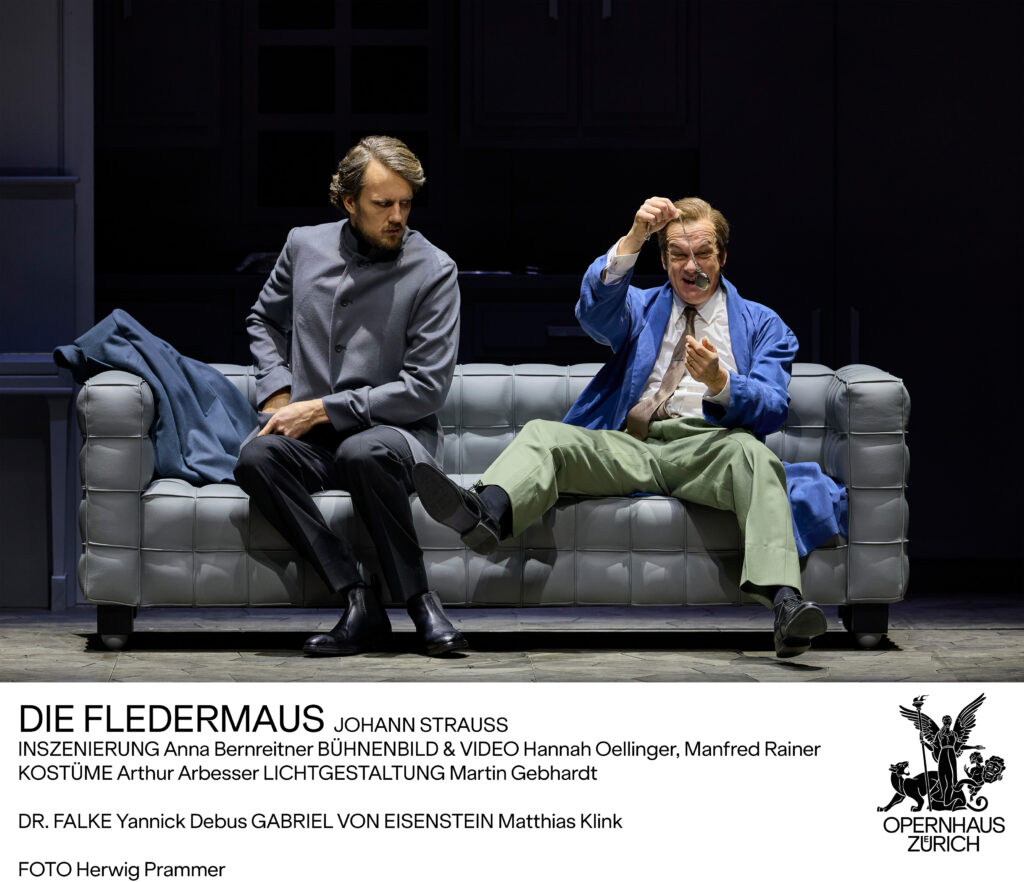

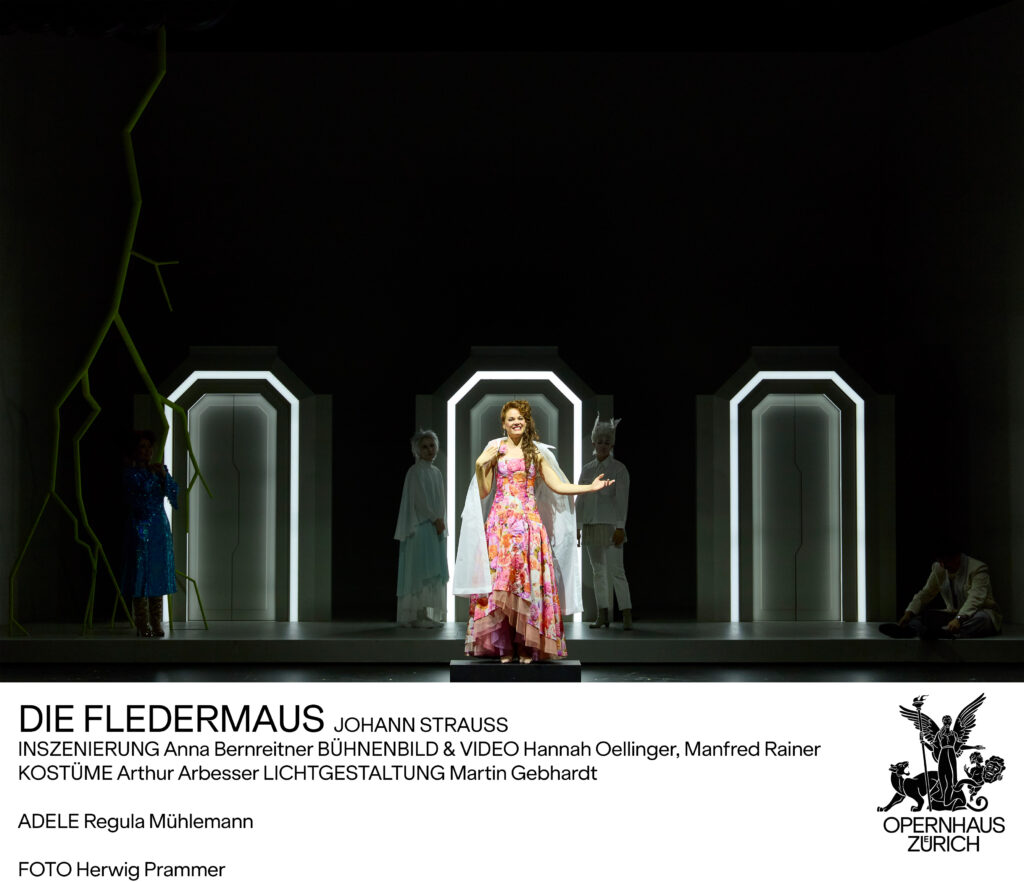

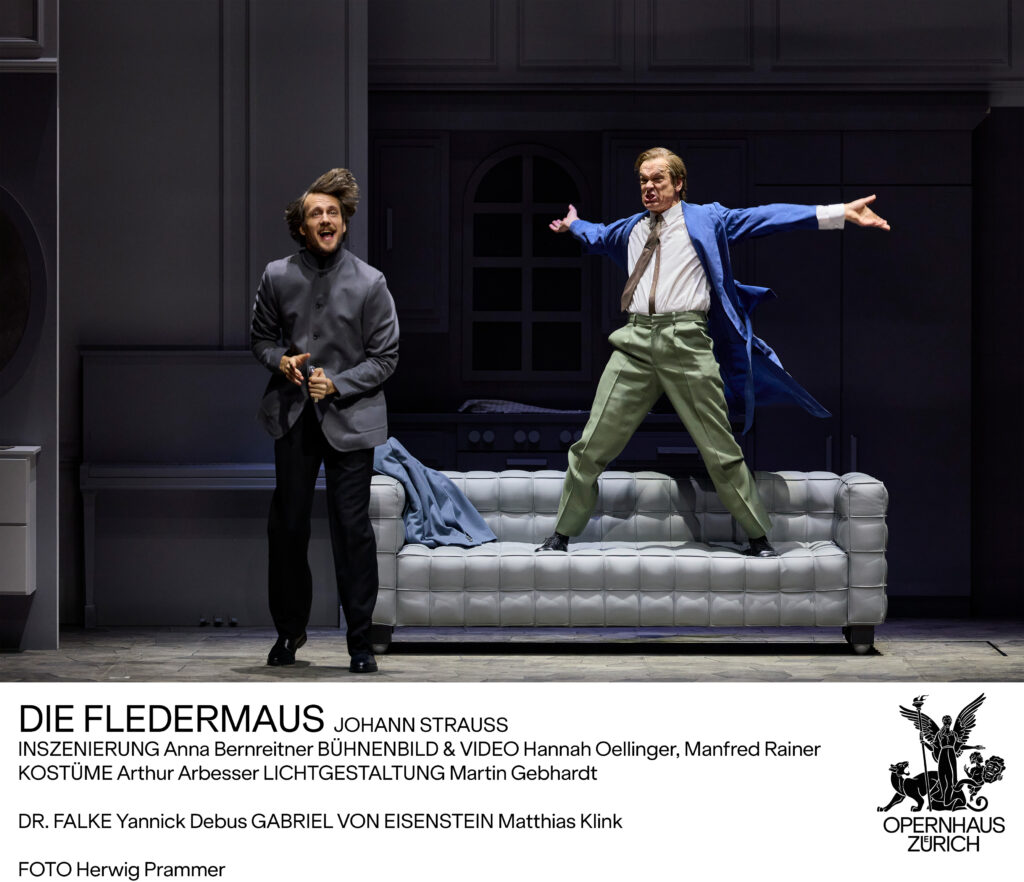

Vocally and dramatically, there was nothing to criticize in the first act. Regula Mühlemann delighted as Adele, her coloratura in the entrance cadenza sparkling effortlessly, her performance charmingly ironic and finely nuanced. Golda Schultz impressed as Rosalinde with excellent diction, a radiant, expressive voice and commanding stage presence. Matthias Klink, as Gabriel von Eisenstein, added a pointed accent with his wonderfully exasperated acting, while Nathan Haller gave Dr Blind a delightfully bumbling quality, demonstrating a fine sense of comedy. Yannick Debus brought charm and sophistication to Dr Falke, and Ruben Drole was equally convincing as prison governor Frank, whose resonant singing and sonorous speaking voice lent the character an ideal blend of humor and authority.

Overwhelming visual design

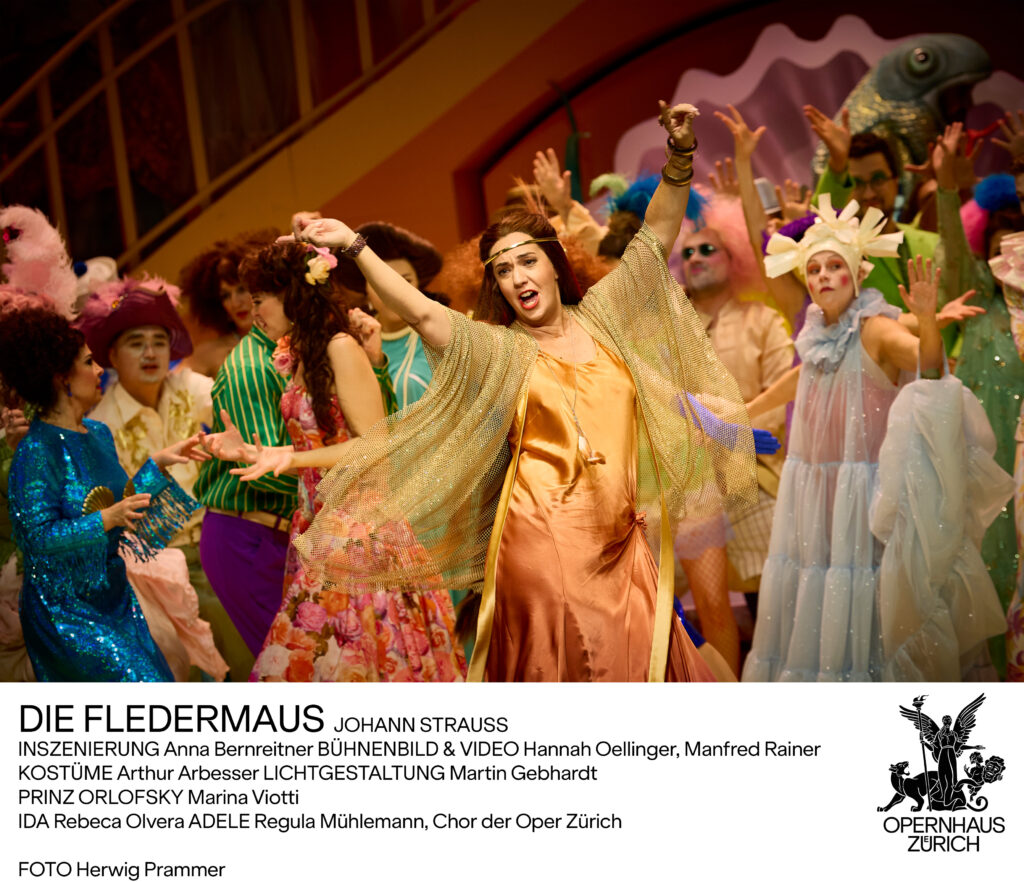

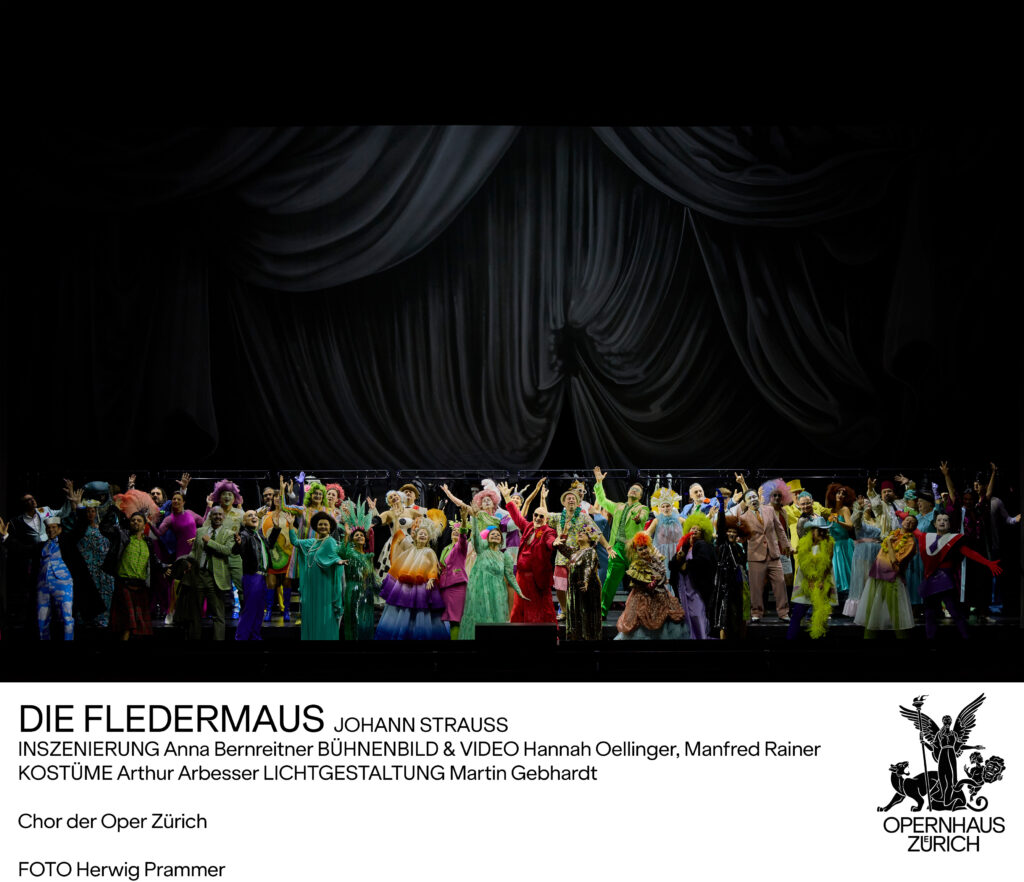

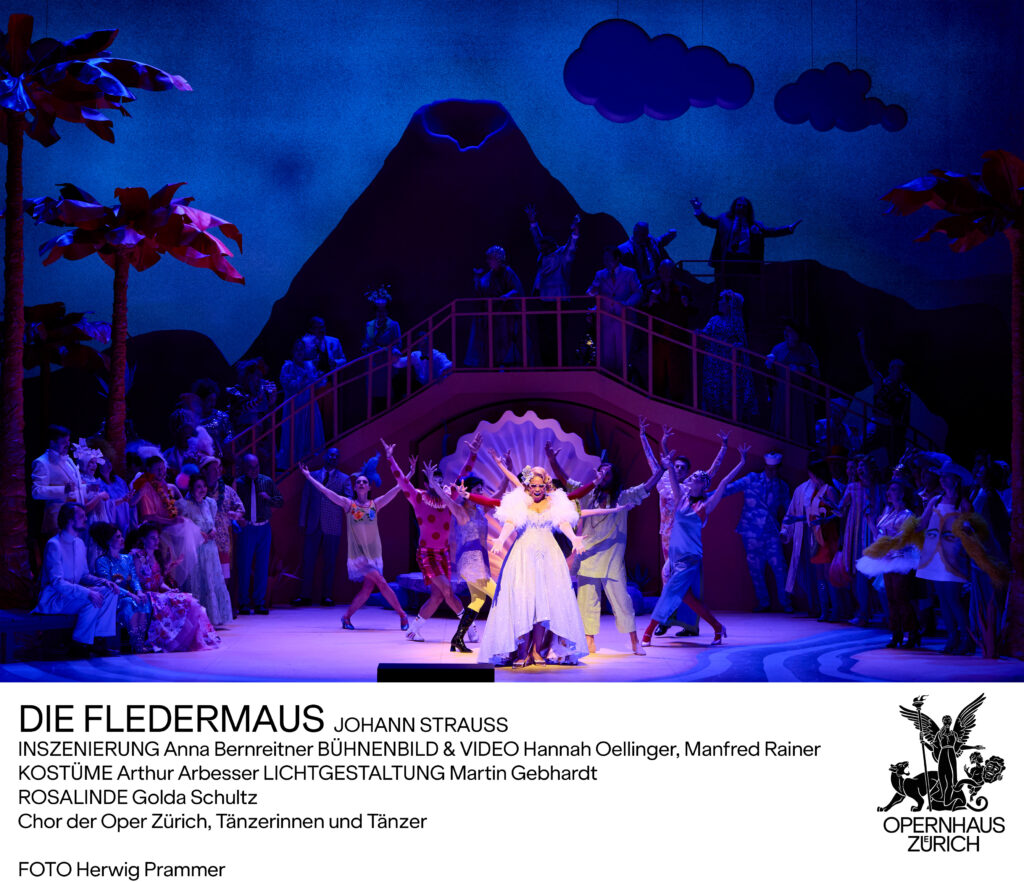

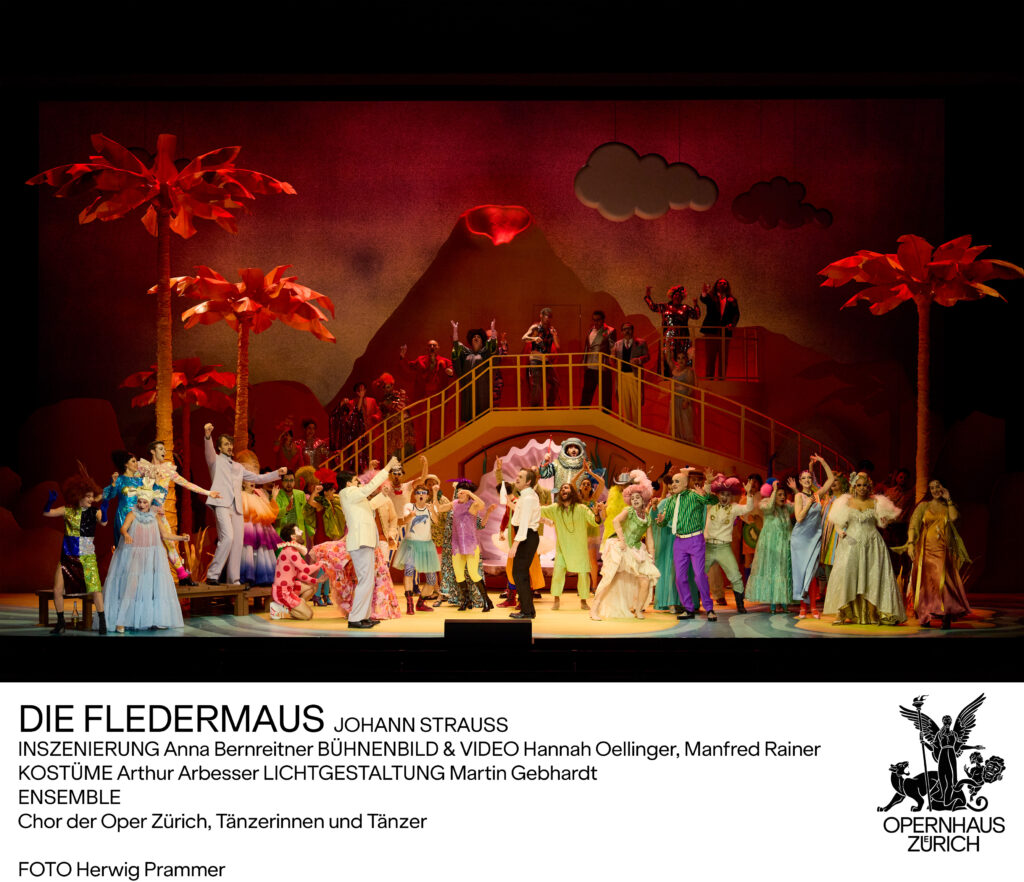

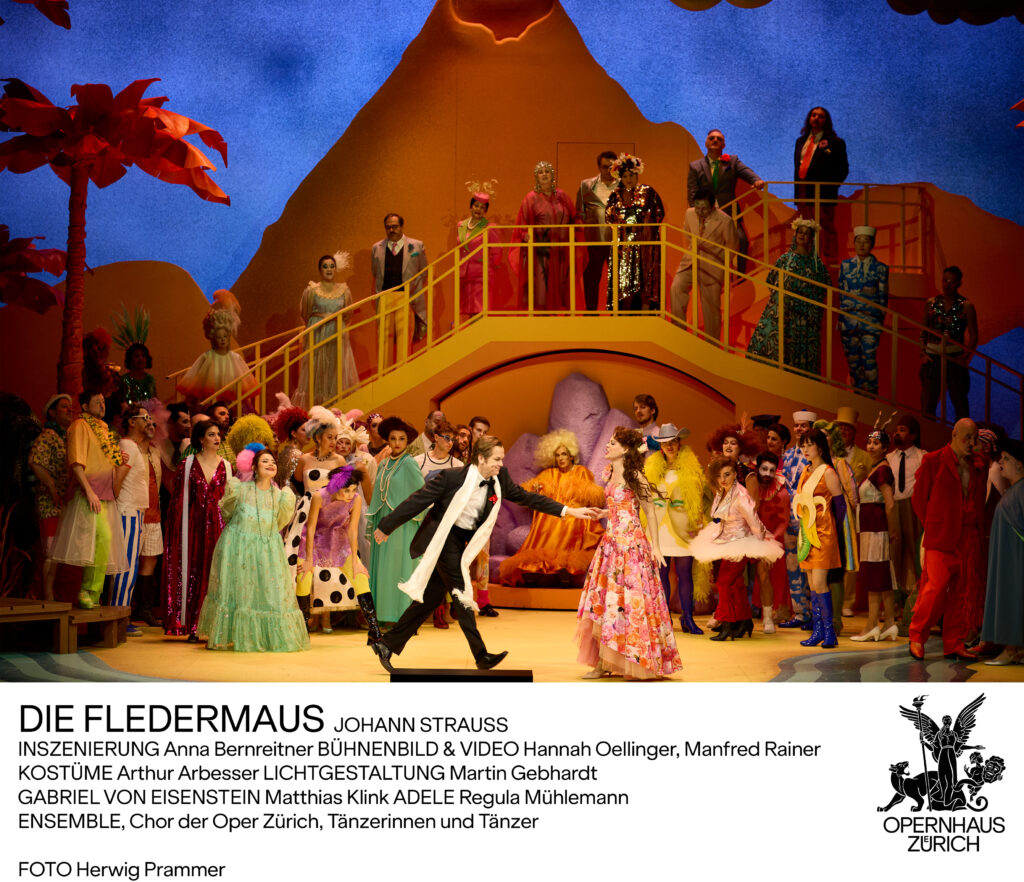

The second act dazzled with its overwhelming visual design (set: Hannah Oellinger, Manfred Rainer; lighting: Martin Gebhardt). The bold colors, especially the orange-red hues, immediately lifted the mood. The chorus appeared in a multitude of imaginative costumes (costumes: Arthur Arbesser), each a small work of art. This visual opulence rightly drew spontaneous applause. The Zurich Opera Chorus impressed not only with vocal brilliance (chorus master: Ernst Raffelsberger) but also with remarkable stage presence, once again becoming one of the evening’s secret stars.

Rebeca Olvera added fresh energy and a clear soprano as Ida. Marina Viotti’s Prince Orlofsky was portrayed with a deliberately exaggerated French accent, her warm, free-flowing voice shining in the first verse of “Ich lade gern mir Gäste ein.” For the second verse, she transformed into a “Dame Edna” figure, singing with a deliberately rasping tone and English accent. The effect was amusing, though musically her natural voice would have been preferable at this point. As she extended the elderly lady persona, the joke gradually lost its impact. Later, Viotti appeared as a Balearic hippie, with long, loose hair and a summery, playful air, even singing in Spanish at one point. The musical interlude of the “Mambo” from West Side Story was unexpected, but thanks to the orchestra’s brilliant percussion and rhythmic precision, it worked surprisingly well.

Regula Mühlemann shone as ever in “Mein Herr Marquis,” her interpretation combining lightness, technical precision, and deft comic timing. An impromptu “Brava!” from the audience underlined the enthusiasm.

Golda Schultz’s performance as Rosalinde in the Csárdás was magnificent. Emerging impressively from an opening shell, she shaped the slow introduction with feeling and beautifully graded dynamics; in the faster section, she impressed with energy and controlled power. She invested the word “Feuer” (“fire”) with infectious, life-affirming vehemence. It was a pity, though, that the central coloratura section was omitted. Nevertheless, the remaining passages, especially the coloratura and the final sustained high D, were flawless and striking.

The intermezzo after the Csárdás, danced wildly to “Unter Donner und Blitz” (choreography: Ramses Sigl), created a New Year’s Eve atmosphere; for a moment, one felt as if the turn of the year was imminent. The scene was colorful and energetic, and the performers seemed to be enjoying themselves on stage as much as the audience in the auditorium.

Between the second and third acts, an unexpected version of the “Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka” was heard, into which a symphonic work with Latin American rhythms and brilliant percussion was woven. The ballet (Sara Pennella, Sophie Melem, Gabriela Hinkova, Sara Peña, Pietro Cono Genova, Roberto Tallarigo, Daniele Romano, Lukas Bisculm) delighted with a spirited, humorous dance routine. The seamless transitions between the musical worlds were virtuosically crafted and must have been extremely challenging to realize – the orchestra mastered them with impressive assurance.

“Space prison”

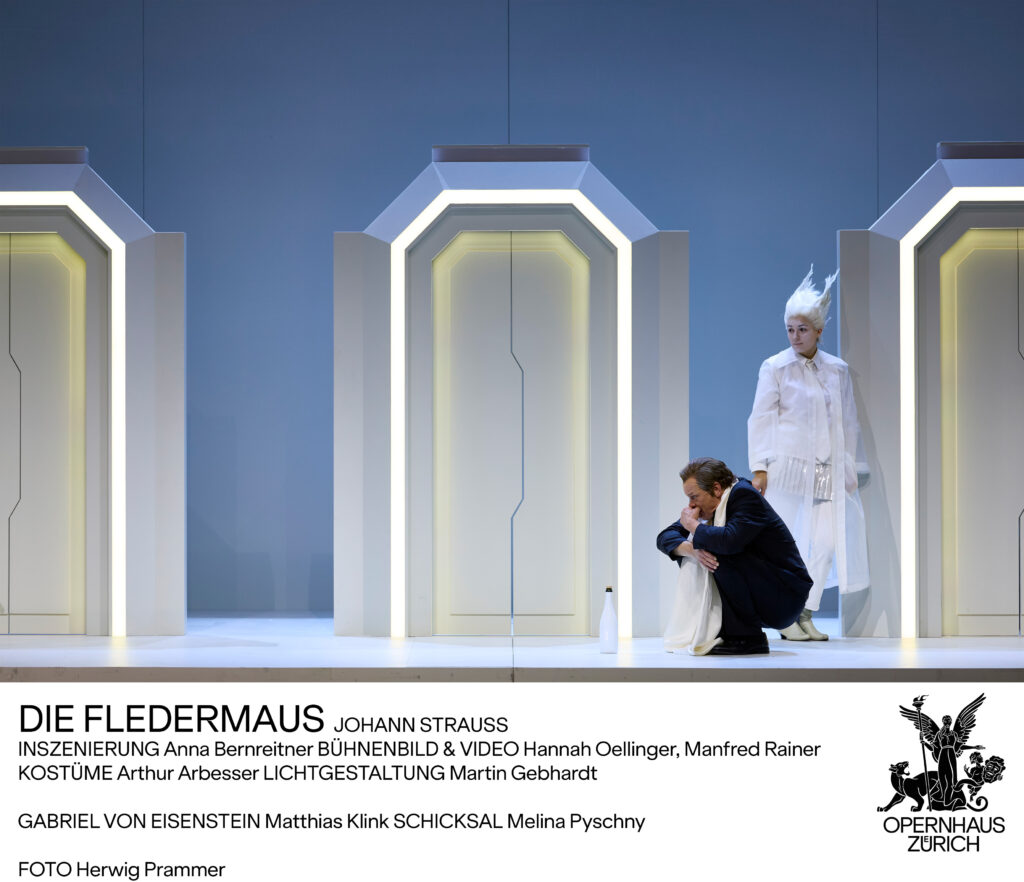

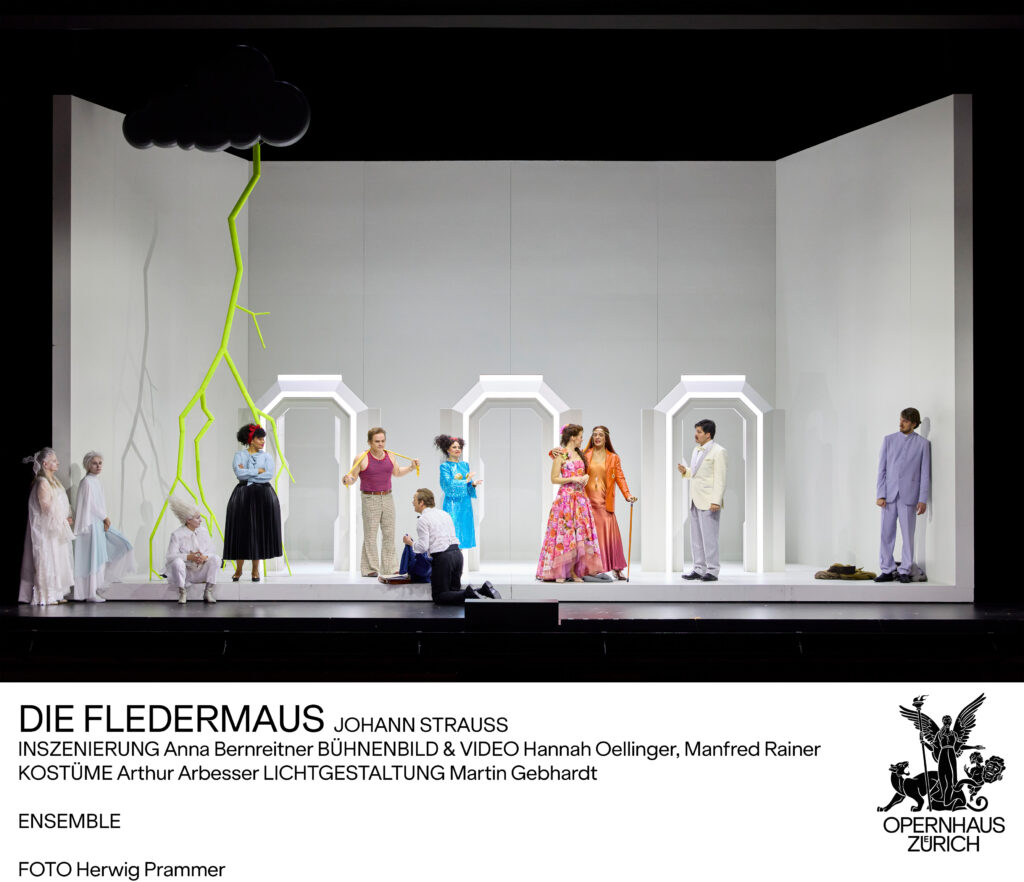

The third act was set in a futuristic, science-fiction-like “space prison” and opened by the three Norns: Skuld (Lucia Kotikova), Verdandi (Melina Pyschny) and Urd (Barbara Grimm). They replaced the traditional Frosch – a thoroughly successful idea, as this character often comes across as embarrassing or “cringe-worthy” in many productions. The texts by satirist Patti Basler provided political wit, charming barbs, and numerous local references. Barbara Grimm’s switching between standard German and Bernese dialect elicited much laughter from the audience. Only a repeatedly used animal welfare joke wore thin after a while.

A minor linguistic slip deserves mention: one of the Norns speaking standard German said “Züricher” instead of “Zürcher”. When “Züricher” is uttered on a Zurich stage, local ears (without the “i”, mind you) inevitably twitch. This faux pas provoked discreet murmurs of disapproval in the immediate vicinity.

Second and third verses swapped

Regula Mühlemann’s rendition of the couplet “Spiel ich die Unschuld vom Lande” was wonderful. Notably, the second and third verses were swapped – presumably so that Mühlemann could conclude the couplet as queen. From a musical and dramatic perspective, however, we preferred the original order; as it was, the unfamiliar ending in this sequence felt somewhat abrupt. The enthusiastic applause from the audience, however, was undiminished.

The operetta’s finale – with the chorus entering the stalls during “O Fledermaus, O Fledermaus”, Rosalinde’s unexpected refusal to forgive Eisenstein, and the lively final chorus “Champagner hat’s verschuldet” – culminated in a festive, rousing conclusion, crowned by a radiant high D, held jointly by Golda Schultz and Regula Mühlemann. The atmosphere was so exuberant that one could easily imagine oneself at a New Year’s Eve performance, convinced that the new year was about to begin.

The audience responded with consistent enthusiasm, even if a full standing ovation did not materialize. Musically and theatrically – especially in the direction of the principals and the choreography (direction: Anna Bernreitner, dramaturgy: Jana Beckmann) – the work was of an extremely high standard. One had the impression of extremely thorough rehearsal, which had brought great enjoyment to all involved, and of an authentic creative flow that never felt forced. The isolated boos for Patti Basler and the production team at the curtain call were, to us, incomprehensible.

We can warmly recommend a (New Year’s Eve) performance of this production.