An Inaccessible World

Bayreuth’s misrepresented Lohengrin

“As man stands to Nature

so stands Art to Man.”

R. Wagner, The Art‑Work of the Future

LOHENGRIN

In its disquieting essence, the Prelude to Lohengrin seems to call out to us, only to reveal that the world it represents will remain inaccessible. Musically, it induces meditation, deep sleep, and timelessly so until it brings us back to our waking senses – far from its distant other-land. A knight before us will hint at his mysterious origins several times, and we sense that his existence in this our world is ephemeral, lofty, yet his stay poses no limits upon himself during his knightly mission; that of saving a woman, Elsa, by freeing her from false accusations. At the end of the opera, the same music becomes less esoteric as it seems to explain itself, though strangely not necessarily through the words of Lohengrin, as if they were not needed. His journey within our society has come full circle, as it did for Wagner himself, who somehow put off writing the music for the Prelude until last, though its beginning notes are inspired from Lohengrin’s own Grail Narration aria, “In fernem Land.” The composer unconsciously guarded the secret of the Order of the Holy Knights until now, as revealing all would have had it shun itself to our uninitiated eyes, on pain of Lohengrin’s abandoning us. This so for all what is ethereal, what must come across during a performance in depicting the purity of incandescent light, known in other spiritual circles as Nirvana. For one such as Wagner, this heightened state allows Nature in its original ambiance to turn into Art.

What is immediately closer to us is the theme of human love as the knight’s purpose in life is to live by codes of chivalry. A King and his populace will soon understand that the worlds of the Grail and the Duchy of Brabant cannot embrace each other, and that our reality must continue without the grace of goodness swirling among us. Lohengrin, conscious of that sentiment in his ethical makeup, will even pursue human existence through marriage, and will even find happiness at Elsa’s side. This Medieval epic poem steeped in legend does take on aspects of a fable, more so if we identify the characters as archetypes leaping off the pages of Vladimir Propp’s Morphology of The Folktale. Thus masked so, these are the personality threads that inspired a Wagner ever-faithful to his childhood experiences spent in the theater, materializing not just kings, knights, lovers, along with magical swans and swords, but fluctuating situations that come from enigmatic, unjustified acts as the motivations of these characters not only plea with each other to be understood, but through guilt or insecurity, attempt to reverse all that has gone wrong.

Laced with twists of fate and concealed deception, there remain tragic outcomes for almost everyone, yet the music set to this uncannily illogical text seems to go its own way, and therein Wagner’s profound sentiments in dealing with myth, human fragility and our failure to have Art takes its place in our lives. Whereas, for example, that other Grail opera, Parsifal sweeping in the unreal, except for instances when characters are stung by deception, or Kundry’s hysterics create imbalance among us, remains on a spiritual level, investigating deeper emotions of consciousness. In Lohengrin, the knight dwells in his ethereal land, as if he has little consciousness of how the world functions. His music is all on one plane; his dealings with almost all the others are of a strident, forceful, hateful, destructive nature. So here we have it – a clash of worlds, surreal incongruence in the name of forces of a distant realm assuming a benevolent, protective stance. One realizes why Lohengrin needs special attention to be understood, and why this returning Bayreuth production was fascinating to look at, yet difficult to accept for the multifarious directorial twists that went against the work’s meaning.

Visual Storytelling

Given the ‘tessitura’ of Wagner’s inner visions related to creating his Lohengrin, we have the subtle weaving of canvases which bear the suggestive narratives of the East German painter, Neo Rauch, working with Rosa Loy. Some of us may have seen one of Rauch’s art exhibitions, and immediately sensed the scenes depicted as occupying a ‘tableau vivant’ theatrical space. And yes, now, by vent of this Bayreuth production, here we have created a world of alienation, a sub-theme running through Wagner’s music and libretto. What we have stated thus far now reveals itself through the opera’s scenery: restlessness, inaccessibility, mysteriously esoteric landscapes, and the human yearning to be understood. Labelled by many to be related to Surrealism, Rauch’s paintings may instead share the sense of reality captured through Edward Hopper’s characteristic personages almost imprisoned in a moment of their lives wherein we capture them as they look out, yet inwards. The difference is that Hopper always grasps the sense of waiting, of stillness, of loneliness even when in groups, while Rauch immerses people as socially committed, reacting from within, earnestly striving to communicate a message in the vain hope of changing the world for the better. A knightly objective, sharing that of the knight Lohengrin. Every painting of Rauch, it seems, is a musical photograph of an opera in course.

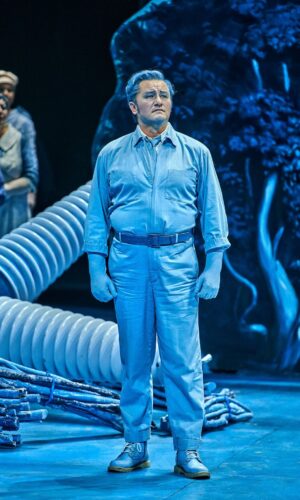

In a poetic way, the beauty of the stage sets illuminates this tale of chivalry in the manner of a children’s book, shades of blue to depict Nature, while hinting at the regality and purity of character that will accept challenges; the duties of a knight are herein evident, involving much work upon oneself in order to understand others. All the space created herein scenically seems to allow Lohengrin to fulfill his goals. His arrival amidst the populace in a square before a hydro-electric generator, the open fields in inclement weather or glorious daybreak, wherein one can gather his bearings, the piazza before the church that celebrates his wedding. Then, the bright orange, almost psychedelic bedroom of the newlyweds in Act II, wherein the psychological fears of Elsa blossom – its seems as much a prince’s castle as anyone could imagine, yet, in its cold sterility, it becomes their claustrophobic mental ward, reminiscent of the cruelty in many Brothers Grimm tales. Thus, all is an extremely wonderful ambiance to confront, scene by scene, yet beneath all the simplicity, we discover a sort of laboratory wherein human emotions are examined. It must be observed that the knight’s Grail boat, here no longer led by a swan, oddly resembled a Batmobile.

A Radical Interpretation, Modestly Enacted

We have focused upon the scenic elements first as the current stage director, Yuval Sharon, stepped in in 2018 to replace another. He had to accept the original concept as far as the sets were concerned, then naturally added his own interpretations in an attempt to modernize Wagner’s message to us. This was his major fault. Much counteracts the composer’s intentions to bring out supposed hidden motivations of the characters which, however, distorted the outcome and departed from the story itself. What was outlandish, and out of tune with the ambiance, could only reveal ‘another’ opera. This Lohengrin unravels itself in a world wherein the audience relates to little on the stage, and our understanding of what we have seen becomes misleading. Thus, much of the stage movement leans to Minimalist evocation, and all that is truly evanescent in this moralistic, knightly tale becomes at best the all-obvious. The problem was that much was based on an examination of the social roles of men and women through today’s society, though the costuming and sets represent a true fairy-tale. It seems as if the stage director and scenographer never met, nor were they able to share their visions. The justification for all refers to a page in the Bayreuth theatre program, where Wagner speaks to us from his pamphlet, A Communication to My Friends of 1851, a year after the Lohengrin premiere Weimar, conducted by Franz Liszt. This is essential to understand the direction this production took. In essence, Wagner returns to his ‘idealized’ woman, sacrificing herself as do Senta and Brunhilde, finding their redemption through love. Wagner discovers through Elsa a complicated feminine reaction wherein she realizes she will lose her beloved, as he has not truly realized the measure of her love, thus causing her insecurities. Yet, a man’s egoism, Lohengrin’s, even in its noblest form, turns to ashes when faced with love, and he can only return to his idyllic realm of knighthood. Here, Wagner’s full-blown Romantic sentiments take hold of his creative spirit as love becomes tragedy. Yet, Elsa here does not die at opera’s end here. No. She is met by a little green man, whom we at first assume to be a symbol of Nature, yet asking why so. We are told it was the blinking figure upon East German traffic lights from Rauch’s upbringing and are left to ourselves to make sense of this. Perhaps Sharon had to accept this figure, squeezing it into his staging.

There is truly too much to say here regarding the liberties taken by Sharon in his insistence on going his own way. We should note that his treatment of the singers and chorus was minimal. Often remaining frozen for long stretches, the entire chorus made single gestures in reaction to a situation, expressing all-too-obvious sentiments. The courtiers and townsfolk were given trite, stock routines, creating inter-personal relations which were at times lost to the audience; one courtier was painting a portrait, others controlled the stances and behavior of their fellow Brabantians. Worst of all, each main scene was carried out by isolated stage actions that only made obvious character motivations obvious. Ortrud (as is Kundry in Parsifal) the bizarre, jealous, and evil magician wife of the conniving knight Telramund lets surface her Lady Macbeth scheming by physically binding him with rope; this goes on for almost the whole scene. It inhibits her from moving in naturally sly ways, showing us how her mind hides her true intentions. She and her husband are here planning, without knowing it, their own end. Sadly, her character’s impact upon us is all-too revealing, and we will never sense the sources of her disguised evilness, as so confirming Shakespeare’s belief that we truly have no way to understand those ‘strange mechanisms of another’s mind.”

Otherworldly Musical and Vocal Enchantment

Maestro Christian Thielemann brought us a beautifully paced reading of the score, drifting tactfully from one emotion to another, reaching into the depths of Wagner’s instigations into human emotion. The Prelude itself gives us hint of this. The dream-like colors of otherworldliness filter through the Festspielhaus hall as nowhere else. All is extremely measured, sweeping in its solemnity. Each note holds on to another, and the suffused tenderness here represents much of the music which, in diverse ways, we will experience as the opera develops. Profoundly moving was the way the woodwinds over-ride the hushed, out-of-nowhere strings of the beginning – the oboes, flutes and clarinets sounding as trumpet calls. This will be so at the end of the opera, where all that is mystic enters into our realities. All through the evening, there is music that we may have instinctively anticipated, holding us in its breadth. There are few excesses, it seems, yet the lyrical utterances sung or not, convey their full meaning. The weight in balancing voices and ensemble singing matched the dramatic instances. A rare reading of the Prelude in 8 minutes, a full minute and a half less than his own recorded versions, proving perhaps that a live performance does condition ‘tempi’, but not because of the relationship with a public – it all may relate to the sensibility of a conductor in placing vibrating sound in a given space, weighing in on capturing the scope of musical sound. It was as moving as it was illuminating, telling of Wagner’s accomplishment in synthesizing an entire work through a single musical idea.

Then, too, we have Lohengrin and Telramund fight their duel in the air, hanging by ropes. This is not because the costumes of all the characters portray them as moths attracted to the electric power plant’s kinetic energy, but because Sharon somehow finds Lohengrin as a Peter Pan archetype, a boy who wishes to never grow up. The final scene, truly difficult to stage, to modernize, was here a true let down. Ortrud does not die but follows close behind Elsa and her resurrected evergreen brother. It was disappointing and untimely to watch Lohengrin, the hero, as he bows out by simply stepping behind lakeside shrubs. When a stage director reads too much into everything, all is separated, deconstructed even; every novelty seems a justification of itself, however detached from the whole. Sharon himself stated that, in principle, all stage directors work toward proving that their initial hypothetical interpretation was valid. He is also convinced that opera “… lies in proximity to poetry, and therefore to our perceptions.” If so, why then over-explain the hidden metaphors of poetic imagery? Isn’t it true that Lohengrin is the most enigmatic of Wagner’s operas, asking us to believe in the clashing realities of a fairy-tale, of myth, of all that unites us through our participation in the family of Man?

Klaus Florian Vogt stepped in for an ailing Piotr Beczala on Augst 9th and was again remarkable not just for his caressing phrasing in his Grail narration aria, but also for his entire delivery of Lohengrin’s essence, ever-wounded through over-sensitivity, then adamant in accepting Telramund’s challenge, upholding knightly values. A true Bayreuth fixture, ever-more ‘heldentenor’ in weight, Vogt is never to be taken for granted. The Elsa of Elza van den Heever was a refined, rewarding performance of a woman in a tricky situation. Musically she remains alone in thought, and confrontation with others is psychologically painful. Add her static positioning throughout this staging, and one can appreciate her intelligent acting wherein she conveys her inherent goodness, damaged by false accusations at court, leading her to call for a knight within her dreams to save her. Her debut Bayreuth performance was satisfactory, solid, and one sensed she would grow vocally in intensity as the opera progressed, as she did. There was girlish fragility in her vocality, so right for the role.

The scheming couple of Telramund and Ortrud seemed made for each other yet also characterized what divided them through their individual human needs. The Act II beginning music leads us directly to them, and we find a weakened Telramund after losing his battle to Lohengrin for Elsa’s hand, as too to a domineering Ortrud, who pleads with him to leave Elsa to her so that she may plant the seeds of doubt, poisoning the validity of Lohengrin’s love. Miina-Liisa Värelä as the pagan sorceress, who also had transformed Elsa’s brother Gottfried into a swan, sang with all the anger and bitterness of her jealousy, yet changed register when needed to charm both Telramund and Elsa. Chilling were her shrill mezzo-soprano sounds of frustration, at times slightly jabbing in acute manner, as also when joining voices with her husband in vowing revenge, something out of Götterdämmerung. It remains to be seen if she will grow vocally in portraying Wagner’s other dramatic roles. Friedrich von Telramund, Olafur Sigurdarson, seemed a bit lackluster in resonance, but the staging might have been responsible for some of this backwardness. He has been an excellent Alberich (Das Rheingold), thus a bit of mystery surrounds his over-all portrayal of the role; his exchanges with Lohengrin in Act I were underplayed. However, the Act II of Elsa, Telramund and Ortrud was conditioned favorably by both the darkness of mysterious clouds of Rauch’s setting and Wagner’s supreme story-telling music.

The other roles were all well-projected and fit in somewhere between the fable and court realities, as did his Herald, Michael Kupfer-Radecky. The four Brabantian nobles, Martin Koch, Gideon Poppe, Felix Pacher, and Martin Suihkonen did not fade into the background but did little to reveal the reasons for their behavior. Compliments, as always, to the Festspiele Orchester, as too the chorus directed by Thomas Eitler de Lint.

In all, we have a Lohengrin as a counter-attack to our current world, which does not serve the intuitions of Wagner in his archetypal, Romantic world. This is a complicated opera, and Wagner was the first to admit that he himself did not understand all of it at first; it crept into his consciousness over time, as with all great works. Lohengrin must be critical of Wagner’s visions, putting before us a fairy-tale imbued in the beauty of a musical ‘spiritus mundi’. A castle or a community’s electric generator may be the key to all Wagner’s artistic ideals. As, too, a Grail on earth, immersed in uncontaminated Nature, and with its swan of wisdom bringing love through peace.